The Vessel

〰️

The Vessel 〰️

By Juno Claffey Hegarty

In 2017, I went on a school trip to the National History Museum’s Archaeology wing on Kildare Street to see their Roman Classical collection. Walking amongst the multitudes of mosaic fragments, amphora, marble, terracotta and plaster, I was struggling to connect. I knew the strides of years that lay between me and the people who made these objects, but their repeated representations in media and culture had rendered me numb to their wonder. Numb to their wonder, until I saw what I am calling The vessel. The vessel is small enough to be held in one hand, it has a handle on one side, a wide base with a slightly thinner mouth and a number of small, rough holes in the bottom. Its material; a mottled, unvarnished clay. The holes imply its use: a strainer of sorts, similar to a colander but not quite so fine. Perhaps for straining larger sediment like grain or oats.

Sketch of the vessel, from memory

Eight years have passed. I started thinking about the vessel again when stuck in a bout of creative block. Trying to remember why making art is important and what it feels like to be touched by a piece of work. The strainer did just that. Sitting amongst the grandeur of the Roman Classical collection and the ancient Irish Treasury collection, the distinct hand-madeness seemed to open my body up to the body of the person who made it. I felt as though it could have been me, hurriedly crafting something that would allow me to strain the water from my pasta. Subsequently, in an attempt to reconnect with my faith in art as a powerful tool of communication, I have begun to search for the vessel. However, despite visits to the museum itself, conversations with staff there and many phone calls and emails with a duty officer named Bernard:

“Hi Juno,

Apologies for the delay in getting back to you.

I have checked a publication on the Classical Collection here in the National Museum, and I have looked at the objects on display, and I could not identify any object with holes in the bottom. There were a number of objects we had on loan, but I checked, and they were all figurines.

I also checked the Egyptian Exhibition with no luck.

I am sorry we could not identify the object for you. However, please do call in and have a look at the exhibition. As I noted when we spoke on the phone, that exhibition has not changed since you were last here.

Best of wishes,

Bernard” (National Museum of Ireland, Antiquities Duty Officer 2024)

I have yet to find it. Not only is my process of searching essentially an attempt at making or finding a utopia, but in many ways, the physicality and effect of the vessel are exemplary of the ethos and various characteristics of improvisation.

Any conversation or interaction we have with one another contains a degree of the unknown, as we learn this degree may decrease, but improvisation is a key foundation of socialisation. Furthermore, any aspect of society is upheld by human relationships insofar as they form an interdependent ecology, and we must communicate effectively with each other in order to enact change of any kind. Without this functioning and live conversation, differing worlds do not have the opportunity to interact.

The strainer, though not apparently a direct product of improvisatory practices in its construction, carries this same quality of interdependent communication in its existence through generations of humanity. As an artifact, it assumes the responsibility of representing one league of humanity to another. Not only representing the presence of a people but their thoughts, actions and ways of being, as it strains through to now. Perhaps the vessel is not so much a utopia as it is a heterotopia. A concept popularised by Foucault, a heterotopia is a space that contains or defines ‘otherness’ from the space around it, often a physical structure or object within a society with the purpose of other. The vessel exists as a holding space both in form and function. According to Heidegger’s ‘The Thing’, the beingness of a “jug” is not its walls and floor but the void created by them. Upon pouring water into the “jug”, it does not flow into the walls but between them, filling the hole. Therefore, the beingness of the object is in its holding.

The vessel, in its physical form and its poetics have allowed for a space of consideration and function other than its intended use. Similarly again, many improvisatory practices operate on the basis that improvisation creates a safe space for the subversion of expected artistic narratives. The vessel then functions as a heterotopia in the same way as improvisation does; both are spaces that safely allow for otherness and therefore are a tool that fights oppression and authoritarianism.

This notion of social responsibility is present throughout improvisation. In this moment of stepping into an unguided space artistically, one has an obligation, to themselves and others, to make this space a safe one for failure. As these moments are often informed by “feelings, unspoken and unthought” (Fischlin.D, 2013), what is informing such a practice is what lies just under the surface: thoughts, feelings, memories and experiences not directly addressed in everyday life. Thus, the responsibility exists here to honour that vulnerability in the self and others, if only to maintain the very space where improvisation exists.

Rule number seven of the Dogme 95 “Vow of Chastity” reads as follows:

“Temporal and geographical alienation are forbidden. (That is to say that the film takes place here and now.)”

(Von Trier. L, Vinterberg. T, 1995)

This reference to “temporal alienation” is key in improvisation, a practice that encourages immediacy and presence in acts of creation. My strainer warps the experience of time in a similar way, presenting it in one long, viewable line by effectively communicating across millennia. Perhaps, in seeking out the vessel that I remember so clearly, I too am trying to bend the rules of time, to find a way back to my sixteen-year-old self. In a time so fraught with worldwide political corruption and atrocity, maybe I am attempting to reach back and take hold of the faith I once had in art and politics. Simultaneously, the vessel reaches forward in time, extending a hand through thousands of years in search of the same utopia.

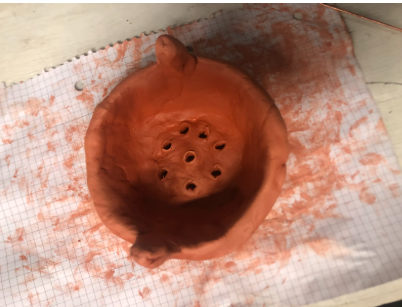

My attempt at recreating the vessel from memory

This adds a layer of risk to an improvisation practice, improvisers that have studied extensively in their field must then bear the burden of representing the depth of the culture within which they practice (Waterman. E, 2015). The ancestry and heritage of a culture are brought in on the risk of improvisation, thus creating higher stakes while simultaneously supporting the improviser through their study.

The vessel is burdened with a similar responsibility: to represent the lives of a people by simply being. The archive, be it objects, images, text or other data, can never be separated from those who constructed it; the ideology of the archivist is always present. The museum as an archive is an educated guess on the lives of those who came before us and an attempt to understand the lives that we live today. The vessel is part of a wider context that is always up for reinterpretation, its existence can be read with the help of years of study, but ultimately, we can never know the past. I can stand in a museum and feel the years of humanity associated with a little strainer, I can feel that I know the person who made it, that it could have been me, but the truth of its existence remains obscured by time.

As it stands, I have not yet found the vessel I swear to have seen, however, the search has given me a great deal of meaning. In the moment that I remembered the encounter in the National History Museum, I was very much clutching at straws, deadlines closing in, and my confidence wavering. To improvise is to embark on an act of making or doing without predetermined plans or instructions, without knowing the outcome. This act, be it a piece of music, a conversation or an object, opens up a space of trust where vulnerability can exist and the possibilities for creativity appear endless.

Just as I have been reaching back 2000 years for answers from a clay strainer, or perhaps just five years for answers from my 16 year old self, improvisation reaches for the utopia of trust, co-creation and hope.

Juno Claffey Hegarty is a filmmaker and writer from Dublin, Ireland. Recently graduated from the National College of Art and Design, her work has been shown at AEMI ‘Dissolutions’ and Oisin Byrne’s ‘Not Marble’. Her practice broadly explores identity and its manifestations in physical space through video, writing (narrative and prose), digital construction and sculptural elements. While the work varies in form, narrative structure and humour are consistent key elements. Often rooted in the mundane and starting from a personal experience or event expanded, through the making process, into a story. These stories are often found through the examination of an object or character (seeing these as one in the same; interchangeable). This personal element leaves an emotional residue that she does not ‘produce’ into her work; queerness, anxiety, tenderness.

Postscript

Juno’s work “The Vessel” is a deeply personal, contemplative response to her engagement with core concepts in critical improvisation studies in the framework of the NCAD elective course “Improvisation: Attempts at Making Utopia” – taught by the project's PhD student Judit Csobod – which she attended in the fall of 2024.